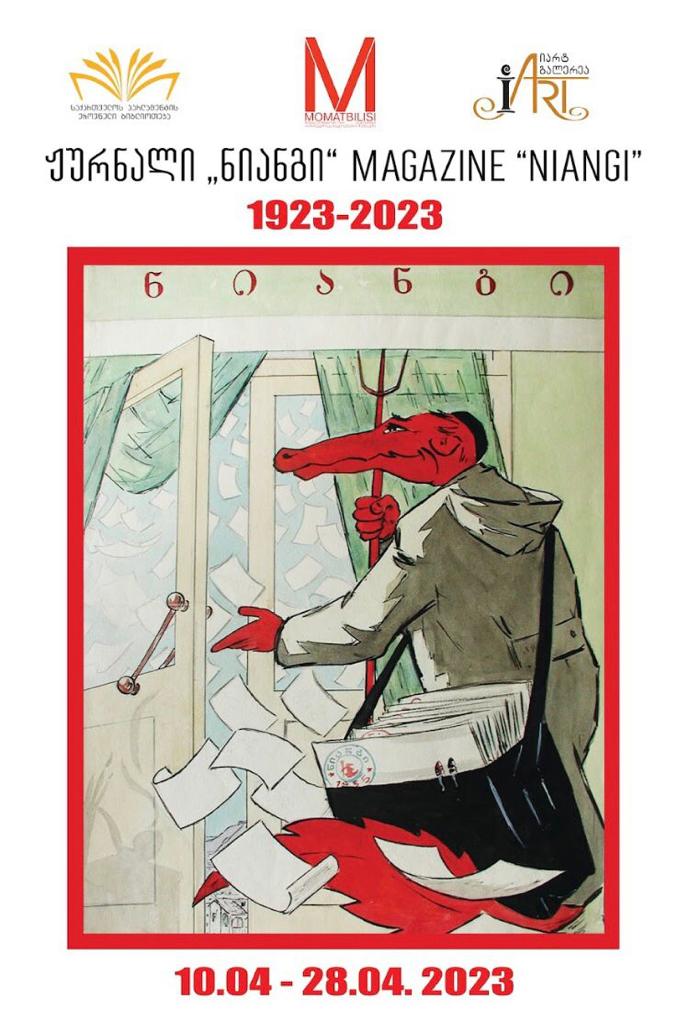

Magazine Crocodile (Niangi)

The Exhibition of Caricatures Dedicated to the 100th Anniversary of the Magazine Crocodile (Niangi)

is a joint project of IArt Gallery and Zurab Tsereteli Museum of Modern Art. The show presents original drawings of the artists affiliated with the magazine and its copies from Andro Kandelaki's family archive as well as the photos from the collection of the National Parliamentary Library of Georgia.

Curators: Ika Bokuchava, Tata Ksovreli

The satirical and humorous magazine Crocodile was founded in Tbilisi in 1923 to exist in parallel to the history of our society of the 20th century, develop to a more sophisticated level in the epochs of diverse political restrictions and prosecutions, fall victim to the challenges and reach the peak of its popularity. The title Crocodile (in Georgian Niangi) was a translation of the name of a Soviet magazine Crocodile, which in 1922 was picked based on a satirical story by Fyodor Dostoevsky.

In 1924-1930 the magazine was published under the name The Tartarus (Leader of the Devils) instead of Crocodile. It was conceived as a tool of state propaganda with a publishing house located at the editorial office of the central newspaper Communist. The publication process involved well-known cultural figures: writers, painters, journalists. At different times editors of the magazine were: Silibistro Tordia, Sandro Euli, Grigol Abashidze, Vakhtang Chelidze, Nodar Dumbadze, Zurghan Gemazashvili, Zaur Bolkvadze and others.

Since the 1990s, publication of the magazine has been put on hold and renewed again several times with the last couple of issues published under the leadership of Irakli Todua in 2011. It's a paradox, but satirical-humorous magazine The Crocodile, which operated under the conditions of multi-level censorship and constant fear of crossing the line, was part of a system it often criticized highlighting its vicious features.

Passing through censorship to deliver any important messages to the readers required the exquisite skills and creative imagination of the author, artist, or writer. In this situation caricature appeared to serve as a unique "weapon". The magazine published amazing works of famous artists, where seemingly light and harmless, humorous, and funny caricatures allowed the attentive readers to enjoy harsh satire.

In a real authoritarian state, a satirical-humorous magazine turned into a reliable source of information and criticism. A mode of constant improvisation offered to establish a certain connection of cultural codes between the authors and the readers.

In the late Soviet period of 1970s and 1980s, popularity of Crocodile reached its peak. Despite a large circulation, it disappeared from the press booths in no time. The stories and jokes from the magazine were frequently quoted in public, in families, and in the groups of the workers.

Due to the prolonged period of existence and a wide range of publications, the phenomenon of Crocodile undoubtedly became part of cultural and historical interest and legacy, providing us with quantitatively and qualitatively rich material for a deep cultural analysis.

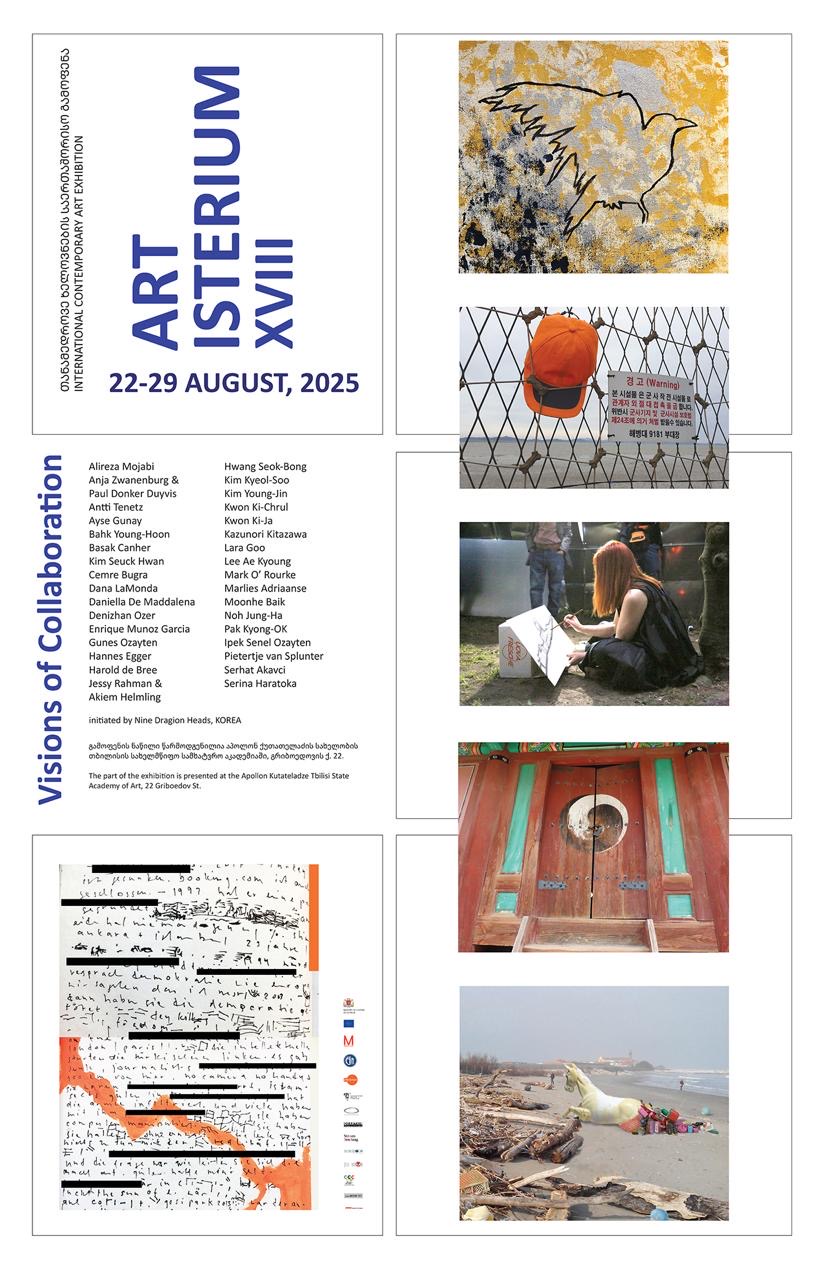

Artisterium 18

August

Poets, Masks, Actors, Ghosts

April